Article by Featured Author

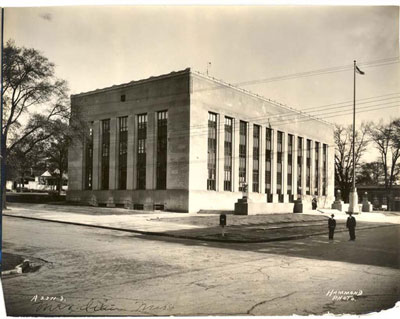

Posted January 2013Erected in 1933 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, the United States courthouse in Meridian, Mississippi will soon be permanently closed. The building, which also houses Meridian’s main Post Office, will remain open, but the courtroom and court facilities, which occupy the upper floors, will be abandoned. And a chapter in Mississippi and American history will be closed.

Courthouse 1933 — National Archives

In September 2012, the Judicial Conference of the United States announced that it would close the Meridian courthouse, along with five others in the Southeast, as a cost-saving measure. (The Meridian courthouse space is leased by the federal judiciary from the General Services Administration, the federal agency responsible for government property; the annual rent is about $115,000.) The judiciary’s most immediate concern was the “fiscal cliff” and the threat of sequestration, which would have cut its budget by $500 million. But cost-saving measures, such as the relinquishment of underused courthouse space, are necessary even in the long term, according to Chief Justice John G. Roberts’s annual report on behalf of the federal judiciary. The courts must do what they can, wrote the Chief Justice, to help right a national fiscal ledger that has “gone awry.” The country avoided the cliff, but the Meridian courthouse could not.

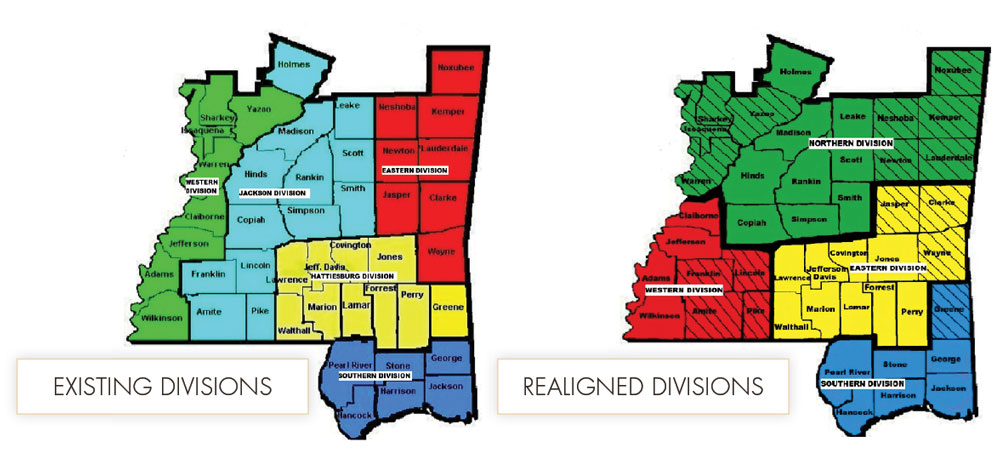

When the doors of Meridian’s federal courthouse are finally closed, on a date that has not been set, the functional impact on court operations in the Southern District of Mississippi should be minimal. A proposal has been made to realign the divisions of the Southern District, eliminating the Eastern Division and dividing its counties into new divisions that are tied to the courthouses situated in Jackson and Hattiesburg. No federal district judge or magistrate judge is stationed in Meridian. There are no court staff members there either, the last ones having left when the clerk’s office closed its Meridian location in the 1990s. (Currently, the clerk’s office maintains a physical presence in Jackson, Hattiesburg, and Gulfport.) Today, most filings are made online. The courtroom and adjacent offices sit vacant unless a judge is visiting from Jackson to conduct court business. Federal trials in Meridian are rare.

Interior Image of Courthouse — District Judge Daniel P. Jordan, III

United States District Judge Daniel P. Jordan, III has presided over five or six trials in Meridian. He called me to discuss the closure from the Meridian courthouse, where he was in the first week of a five-week criminal trial against debris-removal contractors who allegedly defrauded FEMA after Hurricane Katrina. Judge Jordan said that he will miss conducting trials in Meridian. “The courtroom is an impressive setting,” he said, “and the courthouse has served the people of the Eastern Division well for many years.” While he appreciates the architecture and traditional style of the courtroom, Judge Jordan admits that it is a “functionally difficult courtroom” for modern trials; the acoustics are not ideal and the courtroom was not designed with today’s computer technology in mind. Still, he enjoys Meridian cases, which can be conducted without the interruptions and distractions that attend work at his Jackson chambers.

Senior District Judge Tom S. Lee has presided over dozens of cases in Meridian since his appointment to the bench in 1984, including a number of high-profile public corruption cases. He recalls trying an average of six or eight trials per year in Meridian in the 1980s and 1990s, though the number of trials has dwindled significantly in recent years, as it has in all federal courts. The last case that Judge Lee tried in Meridian may turn out to be one of his most significant in terms of its impact on Mississippi law. In Learmonth v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 2009 WL 2252878 (S.D. Miss. July 28, 2009), a federal jury awarded the plaintiff $4,000,000 for injuries stemming from an automobile accident. Judge Lee enforced Mississippi’s statutory caps on noneconomic damages, rejecting the plaintiff’s challenge to the constitutionality of those caps, and remitted the damages by more than $1,000,000. In an appeal that has been closely watched in legal and business circles, the Fifth Circuit certified the constitutional question to the Mississippi Supreme Court, but the Justices declined to answer on procedural grounds. The Fifth Circuit will now decide whether the caps violate Mississippi’s Constitution.

For Meridian practitioners, the symbolic impact of the courthouse closure is significant. Attorney Bill Hammack, who has practiced in Meridian for 30 years, is disappointed that the federal court will no longer have a physical presence in his community. Hammack understands the economic reasons for the closure, noting that the courthouse is infrequently used, but regrets that federal court matters — matters that are often important to the local community and its citizens — will no longer be heard in Meridian.

For many Mississippians, particularly those who lived through the civil rights era and the grim decade of the 1960s, Meridian’s federal courthouse is a symbol that some justice could be done here. This reputation is traced primarily to two suits that challenged Mississippi’s system of segregation — a system so pervasive and notorious that the Fifth Circuit took judicial notice of it in the case of Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962) — and the brutal and murderous tactics that were employed by some to preserve that system. But local attorney William E. Ready, Sr. says the historic significance of the courthouse is broader than just those two suits.

For Ready and some other attorneys in the civil rights era, Meridian’s federal courthouse was a refuge from the biases that prevailed in state courts, a place where they and their clients could receive a fair hearing. Ready, a civil rights attorney and, as the New York Times recently called him, a “dedicated contrarian,” recalls that, because he represented black clients and organizations promoting civil rights and racial equality, he couldn’t get a fair shake in state court in the 1950s and 1960s. The judges and jurors, who were all white in those days, were predisposed to rule against him on account of his civil rights work. In federal court, though, the judges, particularly those at the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, were more evenhanded.

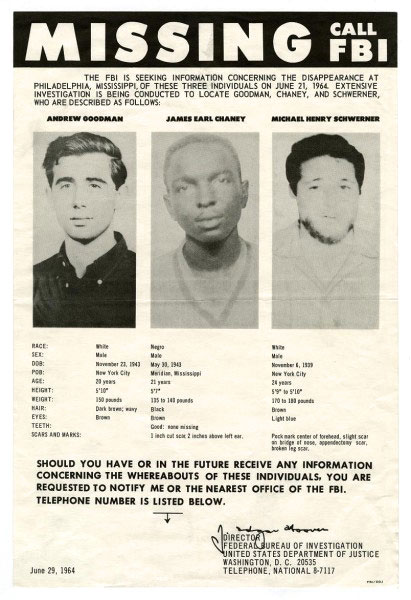

FBI Broadside — Mississippi Department of Archives and History

As for the two significant cases, the first, already noted above, was James Meredith’s suit to integrate the University of Mississippi, filed in the Meridian federal courthouse on May 31, 1961. The initial hearing on Meredith’s request for an injunction requiring Ole Miss to enroll him for the summer term, presided over by District Judge Sidney J. Mize, was conducted in Meridian. Most of the later hearings were held in Jackson, as was the trial. The rest is well-documented history: Meredith prevailed when, after two appeals, the Fifth Circuit reversed Judge Mize and ordered Ole Miss to enroll Meredith as its first black student. (In an unprecedented maneuver to delay the integration, Fifth Circuit Judge Ben Cameron, a Meridian native, issued four stays of the Fifth Circuit’s order, each of which was set aside by Judge John Minor Wisdom, who had written the opinion in Meredith’s favor. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black ultimately set aside Judge Cameron’s stays, finally clearing the way for Meredith’s entry into Ole Miss.)

Coincidentally, only a few weeks after the Judicial Conference announced the closure of the Meridian courthouse, Ole Miss celebrated the 50th anniversary of Meredith’s integration of the University. The United States’s first black attorney general, Eric Holder, gave the keynote address.

The second Meridian suit was the U.S. Justice Department’s prosecution of eighteen Mississippians, many of whom were members of the Ku Klux Klan, for violating or conspiring to violate the civil rights of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, who were murdered in neighboring Neshoba County. Despite the evidence against the defendants, the State of Mississippi refused to prosecute them. The federal government stepped in, and the case was tried in October 1967 by Assistant Attorney General John Doar and U.S. Attorney Robert E. Hauberg, Sr. District Judge William Harold Cox, a college roommate of Senator James Eastland and reputed supporter of segregation, presided over the trial in a no-nonsense manner, surprising some in his refusal to tolerate appeals to white prejudice that were common in state courts. An all-white jury convicted seven of the defendants for violating the victims’ civil rights, a first in Mississippi history.

Norma Bordeaux, who lived in Meridian at the time, served on the federal grand jury that indicted the Klansmen and attended every day of the trial. Bordeaux recalls that the courtroom was full, mostly with the defendants’ family members and supporters. But outside of the courtroom, most people in Meridian were “just not very interested in the case and didn’t pay much attention to it.” She recalls that the local newspaper, The Meridian Star, devoted no special coverage to the trial despite its newsworthy and sensational nature. Bordeaux is sad to see the courthouse close, not only because she believes that the courtroom could still be used today, but because of the civil rights history that it represents.

I grew up in Meridian. My grandfather, Lawrence Rabb, who practiced law there for 50 years, was one of the few white attorneys in Meridian who represented black clients in the 1950s and 1960s. Both of my grandparents were targeted by the Klan for their civil rights activism. In their Meridian home, there is a room dedicated to the display of family photographs; the photos line the walls, from shoulder level to the ceiling. There, among dozens of family photos, hangs a copy of the FBI poster picturing Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman, and seeking information about their disappearance, evidence that some, at least, were paying attention.

The federal courthouse in Meridian will close, its useful life having run its course, but the deeds that were done there will endure.

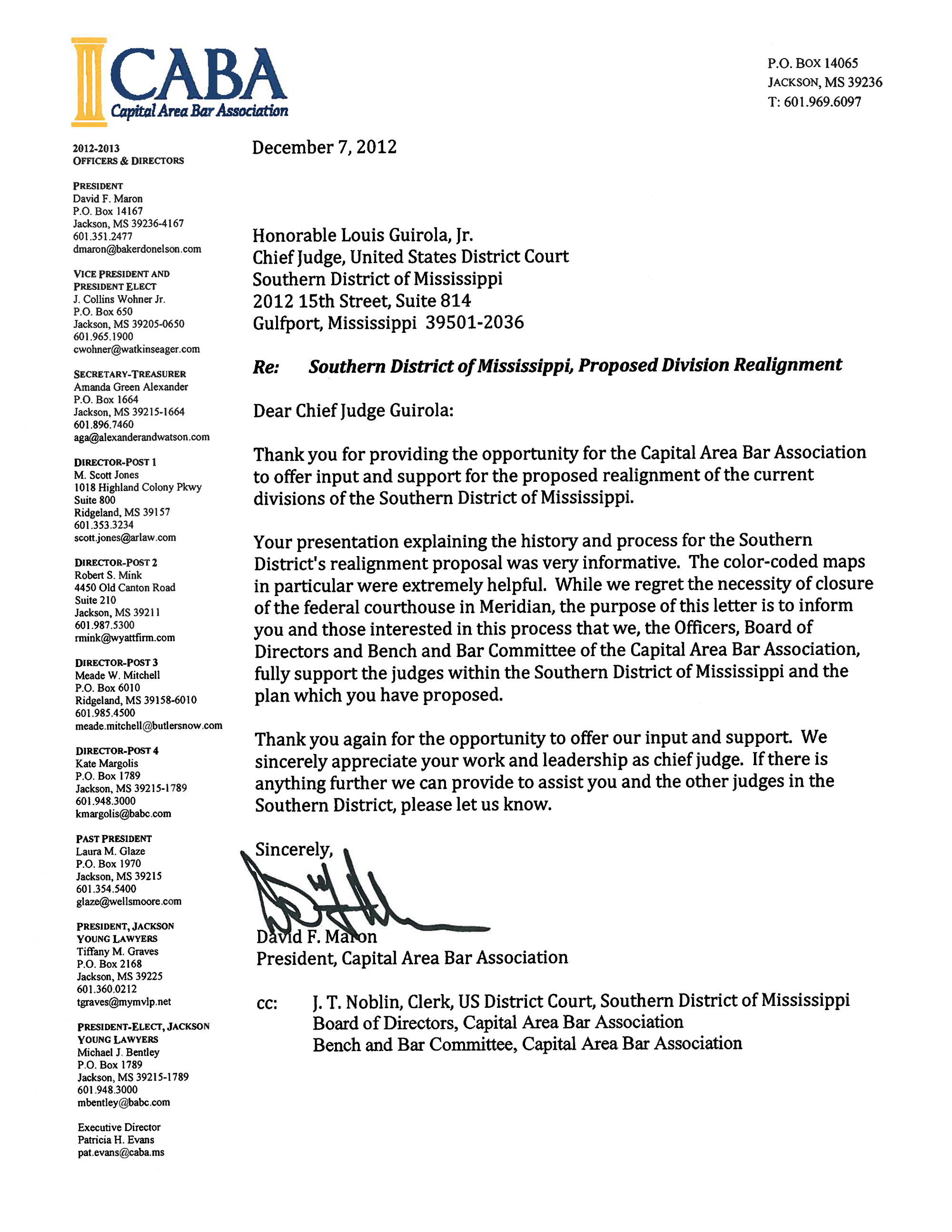

The Fifth Circuit Judicial Council, Judicial Conference of the U.S. Courts, has determined that Meridian Courthouse will be closed. As a result of that closure, the U.S. District Court for Southern District of Mississippi has prepared a proposed plan of realignment reflected in the color-coded maps to the left. CABA’s Board of Directors and Bench and Bar Committee have offered support for the District Court’s plan. That plan has now been submitted to the Fifth Circuit Judicial Counsel for review, which is the next step in a process for legislation that, if approved by the Judicial Conference of the U.S. Courts, will ultimately be submitted to Congress.

CABA Letter of Support for District Realignment