Article by Featured Author

Posted September 2017Editor’s Note: Reprinted with permission of the Virginia Lawyer

Doris Henderson Causey at the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society office.

Doris Henderson Causey, the new president of the Virginia State Bar, has the warm smile and the easy way of an old friend. When asked what people would be most surprised to know about her, she breaks into a football cheer and volunteers laughingly:

“That I was a cheerleader in high school up on top of the pyramid. I was tiny back then. And that I was a band goober in high school and college. I played the saxophone for the Ole Miss band and I played ‘Dixie’ at football games.” She says that she and her husband, who met while they were students at Ole Miss, are still “huge Rebels fans,” and it is easy to imagine her making many a friend at a tailgate party.

In the bustling legal aid office she manages in Richmond, Causey pauses to gently admonish an elderly gentleman waiting with divorce paperwork to “stop getting married, or at least wait until you are divorced,” and as he laughs she points to her executive secretary and says, “You should actually be interviewing her. She is the one who makes it happen around here.”

Located on a rapidly gentrifying section of Broad Street in downtown Richmond, the Central Virginia Legal Aid office shares a glass-windowed storefront with a beauty business called Glam Squad. On one side, young women sit in white leather chairs getting their hair and makeup done for photo sessions for the big day. On the other side, Causey sits to be interviewed in a makeshift space freshly painted after a recent blaze caused when an upstairs resident threw water on a grease fire.

Causey apologizes for the paint smell and settles into a chair right in the store-front window that allows her to smile and wave at the passersby. Across the street, construction workers prepare the site where a statue of Maggie L. Walker, an African American teacher and the first woman ever to charter a bank in the Unites States, will soon be placed.

On June 16 , Causey was inducted as the Virginia State Bar’s 79th president, making her both the bar’s first African American president and the first president to come from Virginia’s Legal Aid community. “A girl in Mississippi doesn’t grow up thinking ‘I’m going to be president of the Virginia bar some-day,’” says Causey. “I see this moment not only as an honor, but as a privilege.”

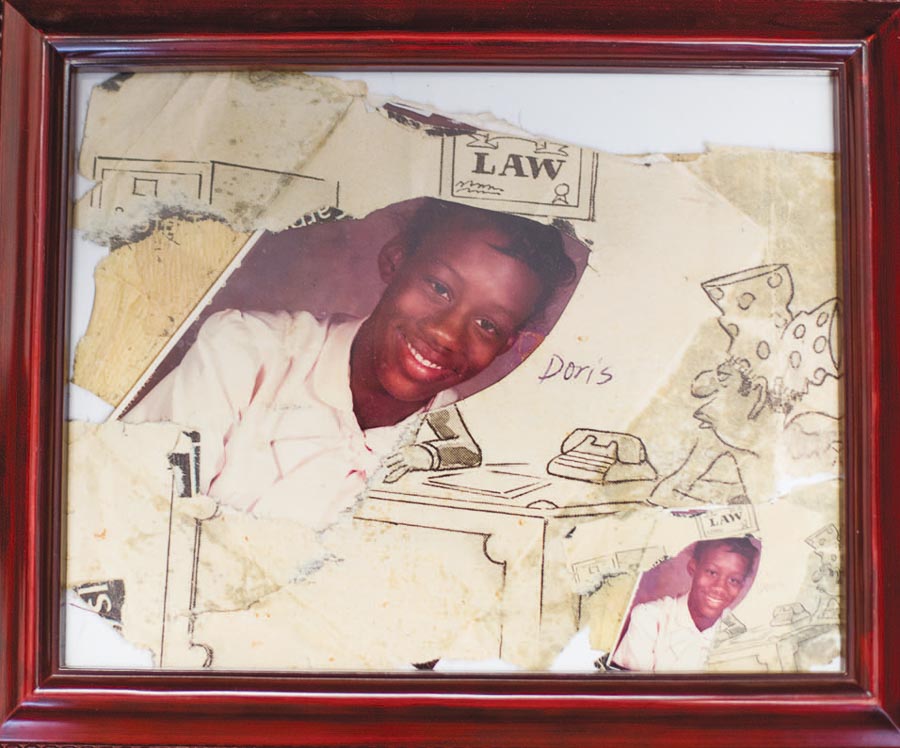

In her office, Causey displays a framed collage she made in third grade of herself as a lawyer when her class was asked to create what they wanted to be when they grew up. Causey says she knew she wanted to be a lawyer mostly because of the powerful influence famed civil rights lawyer Alvin O. Chambliss Jr. had on her family. Causey, the young-est of six children, grew up in Oxford, Mississippi, home of William Faulkner and the University of Mississippi —where Causey’s mother was a professor of education, and her father taught shop at Oxford High School. Chambliss, often described as “the last original civil rights attorney in America,” was a close friend of her parents who often came to dinner and expounded on his latest causes.

Doris Henderson Causey with her husband, Tracy Causey, and their children: Caleb, Jillian, and Joshua.

“He was always suing someone trying to make things fair in Mississippi,” says Causey. “He was trying to make sure that schools had black athletes, black cheerleaders, that everyone had the same equipment and the same chance to do things. Sometimes he was even suing my mother in her capacity on the Oxford City school board.”

Chambliss is best known for his 30-year role in Ayers v. Barbour, which sought to redress Mississippi’s legacy of underfunding historically black universities. He instilled in Causey not only an interest in justice and the law, but also an appreciation for legal aid. “I saw Chambliss, Buck Buchanan, and Ava Jackson in small town Mississippi working to help people, to change people’s lives,” she says. Chambliss’ wife, Josephine, also shaped Causey. She was Causey’s 7th grade math teacher, and it was her influence and excellent math skills that led Causey to graduate from Ole Miss with a double major in political science and mathematics and a desire to teach math. Causey went on to get her master’s degree in education and began a career as an educator. “Teaching was and is my first love,” says Causey. Speaking of her mother and Josephine Chambliss and their role in molding her goals and ambitions Causey says, “There’s the old saying that ‘Behind every great man is a great woman.’ I’ve often found it to be that behind every great woman achieving her goals there are greater women who inspired them.”

Causey’s mother’s family still owns land in DeKalb, Mississippi, where they started as sharecroppers and ended up owning 340 acres of farmland. According to Causey, who still visits Mississippi every summer, “We call it the country out there. The directions to my grandparents’ house start with, “You turn past the store …’ because there really is no other way to describe it.” After teaching high school and marrying her college sweetheart, Tracy Lee Causey, Doris eventually moved to Texas to fulfill her childhood dream of becoming a lawyer and attended Texas Southern University’s Thurgood Marshall School of Law, so that she could be closer to her sister, who was going through her medical residency at Baylor University and her brother who worked in Houston. Ironically, Alvin Chambliss would end up being her law professor there.

Causey created this collage in third grade showing herself as a lawyer.

Causey made her way to Richmond fifteen years ago via her husband’s career as CEO of the Capital Area Health Network, a group of medical and dental organizations who provide care for low-income and uninsured residents. She and Tracy, who began his career in the Air Force, have three children, Caleb, 15, who loves baseball; Jillian, 10, who has a form of epilepsy called Dravet Syndrome yet remains active in sports; and Joshua, 9, who loves gadgets and movies.

Causey and her husband relocated to Virginia before she ever had a chance to practice in Texas, and she found her-self in a new city with a new profession and like many new lawyers had to figure out where to connect.

After passing the Virginia bar, Causey says she looked for her place in the Richmond legal community and found it at the CVLAS. The CVLAS was my Richmond family. I worked down the street at Robert Walker & Associates and I walked there to volunteer daily. Hon. Marilynn Goss introduced me to the ODBA and they became my family too. The first Annual meeting I went to; there’s Governor Wilder and Elaine Jones and Federal Judges, state supreme court judges, etc. I was awed and I was floored.”

Though she was president of her high school student body and her law school class, and was on the student government at Ole Miss, Causey never had a defined goal to get involved in the bar. Curtis Hairston always said, ‘You need to get involved,’” she recalls. “One day a card came in the mail looking for people to run for bar council, so I did. I was the only woman to get elected, and (VSB executive director) Karen Gould asked me to come meet her. I looked up at all the past presidents of the bar and I saw there were no black presidents, and maybe that’s where it started.”

Of her hopes for the coming year, Causey says, “I want people to see that you too can be a bar leader. I bring a different voice. I bring a different perspective. I will see places where there needs to be some diversity. Some people will say this does not matter, but to people of my race it does. You want to be included. You want to have your say.” Causey refers to her past as a means of explaining the journey that took her from private practice to legal aid. When she graduated from law school she recalls, “My mama said, ‘You going to work in legal aid?’ and I said, ‘No, I want to make some money!’” she finishes with a laugh. But she had grown up watching US Attorneys Calvin “Buck” Buchanan and Ava N. Jackson do considerable good for others with their law degrees. “In small town Mississippi, we saw these lawyers using legal aid to do great things for good people. I started volunteering here at Central Virginia Legal Aid, and it eventually became my profession.” Causey draws the connection between the legal aid community and the bar by saying, “I’m not going to win every case. But I am going to tell someone’s story. There are people being charged $3,000 in rent and deposits who find themselves with rats and filth, and that’s not right. You have to go and argue what’s right, and the bar must argue for what’s right as well. You have to address what’s right.”

“I like that I am the first African American to have this role, the first African American woman, and also that I am the first legal aid lawyer,” Causey says of her historic bar first. “We have seen so many big lawyers have this role — it’s important to show that legal aid lawyers can do it too.”

When asked how she feels about her upcoming year and the role she will forever hold in bar history she says, “I think of myself in this role as: It’s time. I am leading a historic bar where there are lots of traditions, and I am glad I did it. I’m glad I put my name in the hat.”

Central Virginia Legal Aid Society