Article by Featured Author

Posted April 2016Last year marked the 30th anniversary of my class’s graduation from Mississippi College School of Law. There are classmates with whom I regularly talk, others that I hear from only around an anniversary, and some who have disappeared entirely. A big anniversary like this one is kind of like a milestone birthday, in that it is a reason to reflect on life, career, and those magical law school days. It’s funny, what we’ve remembered from law school. Oh, I’m sure there’s some academic content hidden somewhere among the synapses — Pennoyer v. Neff, Rose of Aberlone, Blackacre, and substantive due process (referred to by one Con Law professor as “The Court roams at large”) — but the more vivid memories are the little moments, when our teachers let the Socratic mantle slip to reveal their humanity.

We attended law school during the Cretaceous Period (my son refers to the pre-Internet world as “the Dark Time”), when students were treated like… well, students. We were forbidden, on pain of some undefined, but terrible, something from riding the elevator and, in at least one class, we stood when called upon to summarize a case. Without Facebook or any other media distraction, we actually had only two choices during class: sleep or pay attention. Since sleeping was an option only if you were prescient enough to have staked out a corner seat near the back of the room, most of us had no choice but to look at the professor and at least pretend to be soaking up the lecture. By doing so, we sometimes actually learned the material, but we also observed our teachers enough to recognize their particular, endearing foibles. Along with some specific events that occurred at off-site parties and are best left unrevealed, even after thirty years, those foibles are some of my most favorite memories of law school.

Conversations with Ole Miss graduates convinced me that the faculty there was not without its eccentrics, but I have no personal experience from which to expose them. At MC, one of my favorite professors was Joe Sinclitico, who graduated from Harvard Law School just in time for the stock market crash of ‘29 and, thus, spent his early legal career in collections. In the best tradition of the men of that era, Sinclitico eschewed any skill that might be vaguely labeled “secretarial,” so his wife typed his notes. Apparently, she was less than a perfect typist. Almost every lecture was punctuated at some point by a long pause, during which the Professor would scratch his bald head for a moment, mutter “Dammit, Gracie,” and then take a wild stab at what she meant to type.

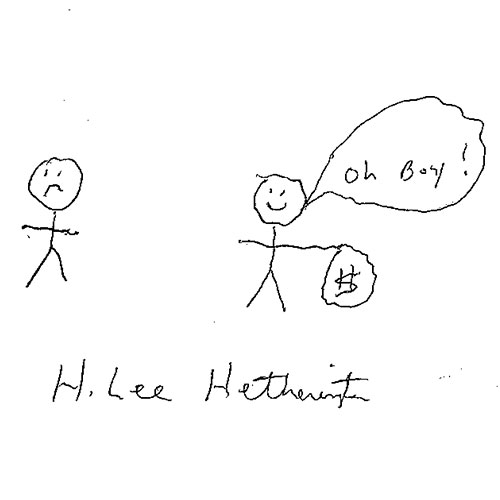

Shirley Jones taught Wills and Estates, and careless draftsmanship was an anathema to her. During the lecture on any case that arose from such carelessness, there would be a point where she would stop, put both hands on her handbag, which inevitably rested on the podium, and ask, “And who put that in the will? The laawyuh did!” My guess is that any former student, when drafting a legal document, strove mightily not to become the subject of one of Professor Jones’s lectures. In a similar vein, I will never consider affirmative defenses to a tort action without remembering Lee Hetherington’s stick figure lecture. One empty-handed figure represented the plaintiff, and one holding a moneybag was the defendant. Between the two, every conceivable defense was pictured as a hurdle, each bigger than the last, and every one designed to keep the first figure from snatching the second one’s money. From Corporations, I learned from Cecile Edwards the punishment for white collar crime, which will always be, for me, her description of doing time at the former federal facility at Eglin, or “fishing in the Alabama River” (as in, “and if you do that, you’ll end up fishing in the Alabama River.”)

An absolute high point of our first year though, when most of us were trying desperately to be neither seen nor heard in class, occurred in Legal Writing. One student had the temerity to 2 complain about the teaching method — where we were given an assignment one week and not told how we were supposed to do it until the following class. Carol West eyeballed the student and said, firmly, “Law School is supposed to be auto-didactic,” whereupon another, even braver, student actually asked, “Then why are we paying $200 a semester hour for it?” Larry Lee, who taught the tax classes, had one of my favorite recurring themes. (At this point, I have been asked to describe Professor Lee. He is, of course, tall and good-looking. His wife, Jane, is even more good-looking, and smart.) He was fond of recounting stories of the escapades of local attorneys, mostly without calling names. At the end of the story, Professor Lee would inevitably lean forward on the podium, grin, and say, “But that’s just lawyers talking at Primos.”

We wondered, every time we heard it, what that phrase actually meant. At that time, the Primos restaurant chain included a café on State Street, across from Baptist Hospital, and another on Capitol Street, downtown, across from the old federal courthouse. Apparently, “Pop” Primos gave each of his children a restaurant to run, and the Capitol Street café was run by Gus. Gus added to the general colorful atmosphere of the place by also running a real estate business from the first booth. It was not uncommon, according to Larry Lee, for Gus to be negotiating some big real estate deal on the phone, move the mouthpiece away, and yell at a waitress, “You need to put some butter on those rolls!”

Primos Café, the Belmont (located across the street from the Governor’s Mansion), and the Mayflower were the gathering places of choice for downtown lawyers. In the days before electronic filing, even before fax machines, many more lawyers were located downtown, from the big firms on Capitol Street to the smaller firms on Tombigbee. Besides breakfast, there was 3 the 10:30 coffee break, lunch, the 2:30 coffee break, and Happy Hour. (For a time, I’m told, the University Club would offer 5¢ beer on Friday afternoons.) You could drop in one of the cafes at mid-morning and see more lawyers there than there were at any local courthouse, or maybe all of the courthouses put together.

In those days, the downtown Post Office was located on the bottom floor of the federal courthouse, and its lobby was another gathering place, as lawyers commonly picked up their own mail. All of these venues gave attorneys an opportunity to meet informally, and, in addition to the inevitable gossip, many disputes were settled there, without judicial intervention. Another advantage, however, to having so many lawyers concentrated downtown was that “breaking news” could be gathered by simply walking down the street. Lee recounted an incident where he passed a fellow attorney standing on a street corner, surrounded by boxes of files. “What’s going on?” Lee asked the lawyer. The lawyer replied, “My partners voted me out of my firm, so I’m moving out.” “Really?” Lee said, “ I hadn’t heard. When did it happen?” “This morning,” the lawyer quipped. “It’s been my experience that it’s never a good idea to stick around.”

Some groups of lawyers, even if they practiced during the time that Lee described, never had this type of daily social intercourse. Neither U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves nor U.S. Magistrate Judge Linda Anderson remembered an equivalent gathering place for African American lawyers, although the Magnolia Bar provided a forum for interaction and regular meetings. Of course, as Judge Anderson recalled, “When I got out of law school, I pretty much knew every black lawyer in the State.” The Mississippi Women Lawyers Association provided similar opportunities for female lawyers; however, that number was also small. Anna Furr, a staff attorney with the federal court who began practicing in 1980, knew most of the State’s female lawyers at that time.

These days, the practice of law, and the geographical dispersion of law firms, has dramatically changed. Although a vestige of the past exists in the Weaver Gore Breakfast Club, which is rumored to meet regularly, most lawyers, on a daily basis, only see other lawyers from their firms. This writer pledges to talk to the lawyers who remain downtown, to see if another meeting place exists; to talk to the lawyers who have moved away, to see if alternate locations have been developed; and to talk to lawyers in the surrounding counties, to see if custom and practice has established local hangouts for lawyers. Law students and new lawyers will also be xaddressed, to determine how they plan to keep in touch with their peers, if they do at all.