Article by Featured Author

Posted January 2012Not my Court, but the court that sits in this building is the most important court for the citizens of Mississippi. To be sure, the Supreme Court of the United States is, in some respects, the most important court in the land…[But] if you were to ask, “What court is most important to the day-to-day life of an American citizen?” it is not my Court; it is the court of that citizen’s state.” The Honorable Antonin Scalia: Associate Justice, Supreme Court of the United States

Remarks at the Dedication Ceremony of the Mississippi Supreme Court Building on May 20, 2011

Why would a U.S. Supreme Court Justice refer to a state court as more important than his own? The reason, as Justice Scalia expounded, is that state law has the most direct, significant impact on citizens’ daily lives. The law on torts, crimes, marriage, and divorce is governed, for the most part, by state law. State courts wrestle with such issues every day. And a state’s highest court has, essentially, the last word on these pivotal matters.

Mississippians are fortunate to have so many highly qualified, devoted men and women serving in the judiciary. These individuals are committed to one endeavor: the fair and efficient administration of justice. That goal remains the same whether the case involves capital murder or a boundary dispute. Our judges recognize that every case affects the life and liberty of the parties before them. They take their work seriously and strive to provide our citizens the best possible system of justice.

To attain the fairest and most efficient judicial system possible, the judiciary is always searching for ways to improve and enhance its services. Drug courts are a primary example. Started in 1999 by then-Circuit Judge Keith Starrett in the 14th Circuit Court District, drug courts offer an alternative to incarceration for certain nonviolent criminals whose offenses are rooted in their addiction to drugs and alcohol. Currently, there are more than 3,000 drug-court enrollees across the state. Participants undergo a rigorous, rehabilitative program that includes substance abuse treatment, close monitoring, and random drug testing. Additionally, they are required to either work or attend school.

The societal impact and taxpayer savings associated with drug courts are tremendous. A ten-year study of the nation’s second oldest drug court showed that criminal recidivism among drug-court participants was nearly thirty-percent less than that of nonparticipating offenders.1 Moreover, drug-court participants are required to pay child support and fines. Last year alone, Mississippi drug-court participants paid a total of $1.7 million in fines; 2 these fines would not have been collected had those individuals been incarcerated. Drug courts save taxpayer money as well. The cost savings compared to incarceration is projected to be about $38 million3 this year—that almost equals the judiciary’s entire general fund appropriation.

There are several other promising initiatives underway. The Mississippi Electronic Courts (MEC) is an electronic document filing and case-management system that improves efficiency, bolsters security, and expands public access. MEC is derived from the e-filing system used by all federal courts. Mississippi received access rights to this multi-million dollar, proven system at no cost. MEC, which is funded by user fees, is in the latter stages of a pilot program that includes the circuit and chancery courts of Madison and Warren counties. Efforts are currently underway to expand MEC into the chancery courts of DeSoto, Holmes, and Yazoo counties, and into the circuit and chancery courts of Harrison County, as well. The goal is for MEC to evolve and mature into a statewide system that will enhance efficiency and save costs.

The judiciary has also taken steps to promote and improve access to justice for all Mississippi citizens. This past year, the Supreme Court revised the Rules of Professional Conduct to allow for limited representation and to relax conflict-check requirements for lawyers who volunteer their services to assist low-income individuals. These rule changes will facilitate opportunities for attorneys across the state to offer pro bono legal services for those who otherwise could not afford representation.

The Commission on Children’s Justice is yet another important initiative. The Commission, co-chaired by Justice Randy G. Pierce and Rankin County Court Judge Thomas Broome, is working to develop a statewide, comprehensive approach to improving the juvenile justice system by coordinating the three branches of government.

Other ongoing efforts include the development of uniform criminal rules and plain language jury instructions.

In sum, the work of the Mississippi Judiciary touches every citizen either directly or indirectly. Our judges appreciate the importance of their duties and are striving to maintain and improve the administration of justice in this state.

Like any other organization, the key to success is quality personnel. For the judiciary, that means strong, experienced, highly trained, and capable judges. We have that now, but there is an ominous trend that threatens the quality of our judiciary for the future. It is, perhaps, the greatest challenge to judicial strength and independence that we face today.

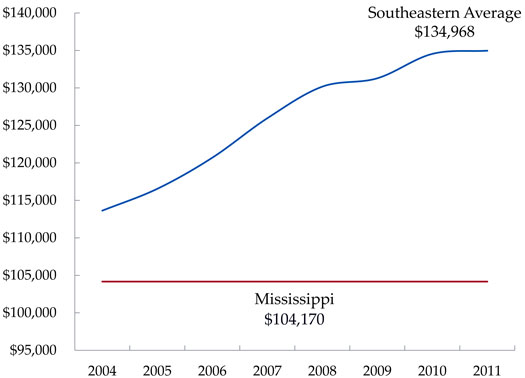

Mississippi’s judges are the lowest paid in the country.4 They have not received a pay increase since 2003. The chart to the left illustrates how Mississippi trial judges’ salaries have compared to the southeastern average since 2004. The disparity is dramatic.

The low level of judicial pay has led to two disturbing trends. First, our courts have experienced an inordinately high rate of turnover in recent years. Twenty-one new judges have taken office during the last two years alone. The low level of pay is one of the main reasons given by departing judges for leaving the bench. Second, the salaries of other important public officials have far outpaced judicial salaries. For example, the Chairman of the Workers’ Compensation Commission earns $112,436 per year, and a Commissioner earns $108,698 annually.5 Both of these salaries are more than the salaries of all the judges on the Court of Appeals who most often review the Commission’s cases. As another example, the Commissioner of Public Safety, who ensures that Mississippi’s laws are enforced, is paid $138,115 per year.6 And the Commissioner of Corrections, who oversees the state prison system, earns $132,760 annually.7 Yet, trial judges, who make the critical decisions in criminal cases, earn substantially less— $104,170 per year. This in no way disparages the essential work and responsibilities of these important public officials; it simply highlights the pressing need for realignment.

Southeastern average is based on the salaries of general-jurisdiction trial court judges in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia, according to the National Center for State Courts’ (NCSC) annual Survey of Judicial Salaries.

Without question, the economic climate makes it difficult to argue for a judicial pay increase at this time. Times are hard for many people across the state. And, certainly, there are countless other private and public-sector employees who are underpaid. Yet, the issue of judicial pay merits serious, immediate attention. Judges make decisions that influence family life, public safety, the economy, and the very nature of our society. Only the best and the brightest should be entrusted with this responsibility.

Yet, current pay levels, which have remained static since 2003, erode our ability to attract and retain such individuals. Though we can never expect to match the salaries available in the private sector, judicial salaries should be high enough to attract and retain competent, highly qualified lawyers. This is really about the health and future of the judicial system in Mississippi.

During the 2012 Legislative Session, the Mississippi Judiciary will propose a judicial pay bill that features three major components. First, the bill implements a four-year, step pay increase for Supreme Court Justices, Court of Appeals Judges, Circuit Court Judges, Chancery Court Judges, and County Court Judges. Trial judges’ pay, for example, would increase from $104,170 to $112,127 in 2013; their salaries would then increase annually until the target compensation of $136,000 is reached in 2016. Second, increased civil filing and appellate court fees are used to fund the pay increases—no general funds are needed! This accomplishes the objective and, at the same time, frees up general fund moneys to be invested elsewhere.

Representatives (PDF) Senators (PDF)

Finally, the bill provides for a periodic review and recommendation by the State Personnel Board concerning adequate levels of pay for justices, judges, staff attorneys, and law clerks. As already noted, judicial pay has been neglected for several years now; this is a recurrent theme. One reason for this is that judges lack a constituency to lobby on their behalf. And the judiciary is ill-suited to do so itself. Judges are often required to interpret or rule upon the constitutionality of legislative enactments. At the same time, they are dependent upon the Legislature for their compensation. This tension poses a real and serious threat to judicial independence. A periodic review by the Personnel Board would ameliorate this problem and ensure that judicial pay is at least considered every four years or so.

Last year, a similar judicial pay measure passed the Senate handily but was defeated in the House by a narrow margin. To ensure a different outcome in the 2012 session, we need the Bar’s help. I encourage each of you to contact your senator and representative and urge them to support the judicial pay bill this next session. Your voice is crucial; it made a difference last year, and I am confident that it will be the deciding difference in the 2012 Regular Session.

The judiciary is not simply another agency, department, or public-improvement project. It is a co-equal, independent branch that fulfills a core function of government. And its impact is far-reaching. Former Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall once stated that, “The judicial department comes home in its effect to every man’s fireside: it passes on his property, his reputation, his life, his all.”8 Given the prominent role of judges in our democratic society, it is imperative that only the best and the brightest occupy these positions of trust. The bottom line is that a competitive level of pay is required to attract and retain such individuals. Without it, the future of our state judiciary is jeopardized.