October 19, 1915 – January 21, 2015

Article by Featured Author

Posted April 2015Chief Justice Harry Walker stopped by my suite in the old Gartin Building that afternoon in late September of 1987. He was making the rounds, a personal visit to each Justice on the Supreme Court of Mississippi, to let us know he had decided to resign. A pleasant enough visit, warm reciprocal expressions of appreciation and best wishes.

And then Harry added, "You know, Roy always wanted to be Chief Justice."

According to custom, Justice Roy Noble Lee, next senior in point of service, would become Chief Justice on October 1, 1987.

Percy Mercer Lee, Roy's father, had briefly held the office in 1964–65. No one doubted that Chief Justice Roy Noble Lee would enlarge and extend his father's legacy.

I recall that first en banc conference with Roy in the Chief's chair. With quiet humanity, Chief Justice Lee shared his vision and pride in, and in the honor and privilege of, service on the Court. His eyes rotated around the table, fixing on one Justice, then the next. He left no one out, as though we were a jury.

A bit stuffy, perhaps. But sincere, real. Noble was not only his middle name. He was also brief. There was work to be done.

I'd had a hard time getting a fix on Justice Roy Noble Lee when I came to the Court back in January of 1983. I have no memory of him at all regarding the cause celebre of the time, the great Separation of Powers case, Alexander v. Allain,1 except that he did not dissent when Chief Justice Neville Patterson produced and led the Court to Mississippi's Marbury v. Madison.

Justice Lee had dissented two years earlier when the Court promulgated the Mississippi Rules of Civil Procedure. Firmly but quietly.2

A less well known case, now largely forgotten, is my point of beginning. A huge controversy had been raging in Central Mississippi over the ad valorem tax revenues available to the Barnett Reservoir and how those monies were being used. Accumulated might be a better word.

I found myself thrust in the middle of a bitter intra-court battle on a matter I knew nothing about. I wasn't sure I cared much either, except that here was a complex case that had to be decided, long briefs to be read, and in short order; also, a massive record on appeal.

Tempers flared within the false quiet on the fourth floor of the old Gartin Building. Then down time, as the combatants retreated to their corners to calm down, and to sulk. No position could command a majority. Months later, righteous and conflicting indignations would erupt again.

The case ultimately was decided by an evenly divided Court,3 one Justice not participating because of conventional judicial recusal policy.

In the end, Chief Justice Patterson asked for two volunteers, one from each foursome, to prepare a per curiam order so the parties and the public would know what it all meant. As the member of the Court with the least interest in the case, I agreed that such a practical exercise was needed, and that I would work with a Justice on the other side to sort it all out.

I quickly found that two of the Justices I had voted with on the merits would not speak to me. I was consorting with evil! The intra-court passions were that high.

In the midst of this, Justice Roy Noble Lee wrote but a page.

"I emphatically agree that the Legislature contemplated … that when all of the funds coming into the district are properly applied, there may or may not be a need for the special two-mill levy provided by [law]."4

For twenty years this two mill levy had produced "revenues of the district [that] steadily increased, aggregating enormous amounts, … [T]here have been corresponding tremendous increases in expenditures by the District for purposes not contemplated or authorized by statute."

Still, Justice Lee would support only a prospective accounting, "with the situation having existed for so long a period of time."5

"Otherwise, in my view, havoc would prevail in the District. Subsequent to that date, there should be an accounting for all funds expended without authority."6

And that was about it. Five paragraphs of substance, buried in the middle of 38 pages of blood red spilled ink. He did not cite a single case. A couple of statutes mentioned but not quoted. No high horse.

Just a strong sense of the core facts, of what was right, and of what was practical.

"ROY NOBLE LEE, Justice, concurring"7 was inscrutable, as was the man. I took notice.

The Summer of 1984 produced a watershed moment in my relationship with Judge Lee. I had drawn the writing assignment in a death penalty case, the tragic but all too familiar late night robbery/murder of a gas station attendant.

The case turned on the recanted testimony of the defendant's half-brother, who had his own serious troubles with the law. At a trial held in July of 1981, the prosecution was allowed to call the half-brother, impeach him with his recanted statement, and then argue the statement as substantive evidence.

It was not until 1986 that Mississippi adopted Miss. R. Evid. 615 which may have influenced the outcome determinative issue, but that is not to the present point.

Consistent with the en banc conference vote, I drafted an opinion, reversing the conviction and remanding the case for a new trial. Another Justice then circulated what I thought a rather intemperate dissent. Scare tactics. Cheap shots.

In 1984 as now public passions ran high in death penalty cases. September of 1983 had seen Mississippi's first execution in 25 years, and many wanted more.

It was known that, personally, I was no friend of capital punishment, though I had by that time voted to affirm a number of death sentences.

Within the Court, once a dissent is drafted, the Justice writing for the Court is given the opportunity to revise the proposed majority opinion so as to address the points made by the dissent. I was comfortable that the majority opinion I had drafted reliably applied the law at the time to the facts of the case.

I sensed I should not rise to the bait tendered by the dissenting Justice. I loathed the thought of letting his diatribe go unanswered.

A few days later, Roy Noble Lee made what may have been his first visit to my office suite in the 18 months I had been on the Court.

"Jimmy, on this Moffett case, let me take care of Judge ____. You don't need to say a thing."

In time another opinion was circulated. "ROY NOBLE LEE, Presiding Justice, specially concurring," and concluding:

"As a district attorney for twelve years in a five-county district, and as a trial lawyer for many years, the writer has encountered and dealt with, dozens of times, the exact questions now before us.

"From my examination of cases and records in this Court for almost nine years, I see little difference in people, defendants and human behavior now from when I began the practice of law. I am confident that so long as judges decide, and attorneys try, cases according to law, society has nothing to fear.

"I concur with the majority opinion."8

I can't remember whether it was immediately, or maybe days later, that I smiled inwardly as I remembered Humphrey Bogart's unforgettable final words to Captain Renault in the movie Casablanca. If Roy Noble Lee was your friend, he had your back.

I'm sure I never thanked Roy enough for giving me cover that day in 1984, as I have never enjoyed before or since.

I did start trying with the deer headlighting case9 that came along four months later. That story has been well told, by Chris Shaw and others.10

Tort liability was a point of high heat within Mississippi legal circles in the 1980s. The Mississippi Trial Lawyers Association was on a roll.

There were recurring pleas for the courts to extend liability, to bend long standing precedents in favor of the plaintiff. Punitive damages were becoming a flash point. Tort reform talk was at least a decade in the future.

Roy Noble Lee was a quiet participant. He would remind us that he had been the first President of MTLA. Roy was not opposed to a plaintiff making a big recovery at the expense of a liability insurance company.

But Justice Lee was slow to support overruling settled tort doctrines to make the law more favorable for MTLA damage suit lawyers. His view was simple. He had been successful with a plaintiff's personal injury practice in the 1960s and early 1970s. A good trial lawyer didn't need a stacked deck to succeed.

And so Roy Noble Lee dissented when the Supreme Court followed the great majority of states in adopting a national standard of care for medical malpractice cases.11 He dissented when Mississippi abrogated interspousal tort immunity,12 again joining a national trend in tort law. And in other similar pro-plaintiff (some would say "more principled" or "more practicably realistic") shifts in the law of torts.

One story says it all about Roy Noble Lee, vintage plaintiff's damage suit trial lawyer. And of his view that a good trial lawyer needed a skill set not taught in law school.

Years ago, perhaps in the late 1960s or early 1970s, Roy represented a plaintiff with "good injuries" and "good liability." The case was being defended by a very able lawyer from Meridian.

The trial date was approaching. The defense wouldn't offer much above nuisance value. Roy was playing it close to the vest. "That's fine. We'll let a jury pass on it."

A couple of days before trial, there was a little movement in the defense offer. Then the day before trial, the lawyers (who knew each other well) talked, exchanged jury instructions, whatever. Roy brought up settlement again.

A protracted discussion took place, punctuated by lunch, "lawyers' lies" and several long distance calls by the defense lawyer to his insurance client. Late that afternoon, the defense finally offered what Roy thought he needed. A handshake sealed the settlement agreement.

After a week or so, the defense lawyer tendered the settlement check, with the customary release and proposed order dismissing the civil action. The settlement check, of course, was deposited into the Lee Law Firm trust account.

And there the matter lay.

A month or so went by. The defense lawyer called. "Roy, I need my settlement papers." Lawyer Lee stalled, apologized. "I'll have them to you before too much longer."

More months passed. No signed settlement papers. More phone calls. More stalling. More apologies.

At one point the defense lawyer was coming through Scott County and stopped by Roy's office. "I've just got to have my settlement papers. My client is furious and needs to close his file."

Understand that each time I heard Roy tell the story it grew a little, was embellished a bit. A fish story of sorts. Roy beaming like a bream.

I'm pretty sure Roy said it was close to a year before he finally sent the release, signed by the plaintiff, back to the defense lawyer, who after reviewing the long awaited papers to be sure all was in order, noticed that the plaintiff's signature had been notarized in France.

The plaintiff had been in France all along. The plaintiff had not been in this country since shortly after the accident, much less in that week leading up to the trial setting, and, despite Roy's best efforts, had made it clear he was never coming back to the United States.

I have it on hearsay authority that the defense lawyer confirmed the story.

Roy enjoyed this "for instance" on what it took to be good trial lawyer as much as any case he ever had. How his eyes twinkled!

Chief Justice Lee had a traditionalist's view of the role of the courts in society, and of the Supreme Court of Mississippi in particular. Percy Mercer Lee had brought his son up right.

As much as he respected the separate office of the other eight Justices, he expected each to live so as to be perceived publicly as a Justice of integrity who respected the traditions and responsibility of the office.

When a judge misbehaved, Roy's vote was never in doubt. En route to removing from office a justice court judge for converting to his own use the funds belonging to civil litigants, Roy once wrote "That office will remain in disrepute as long as respondent occupies it."13

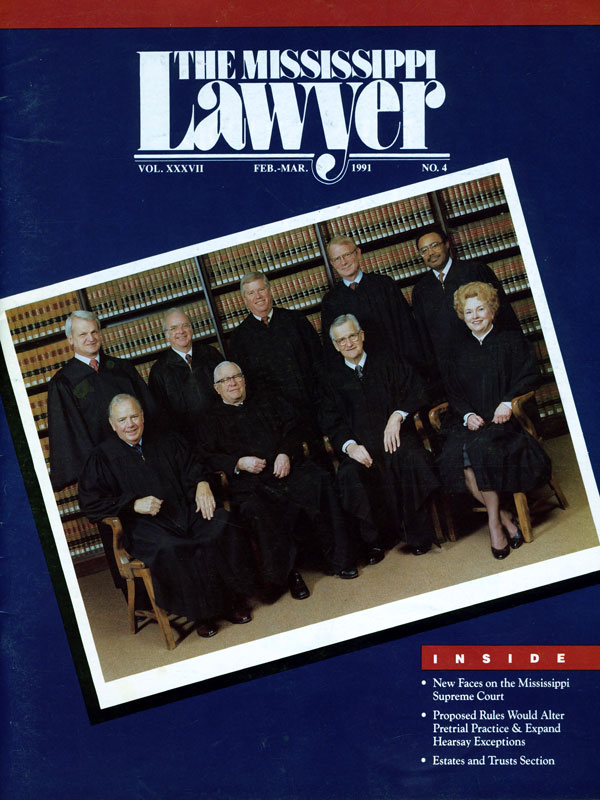

In late 1990, the Court scheduled for a Thursday morning en banc oral argument two cases of great public interest (some would say "political interest").14 After a break following the arguments, the Court convened in en banc conference for the rest of the day.

At the outset, Chief Justice Lee put on his most imposing ex-FBI agent face. A brief, stern command followed. "Everything said in this conference stays in this room. I do not want to read in the papers, hear on the street or hear from any other person in the world a whisper that anyone outside this conference room knows what we have said and done and how we vote on these cases." Or words close to that very clear effect.

As the conference ended, Chief Justice Lee repeated his admonition. He meant it. He expected us to behave as judges, and was within his rights and responsibilities to say so, to demand that we do so.

I drove back to Oxford late that afternoon, as was my practice. Around eight o'clock that evening, I received a telephone call at home from a reporter whom I knew well. He had the tentative vote, and he had it right on each case. I refused to confirm or deny.

I never saw a news story or heard of a TV report of what my reporter friend "knew." I never mentioned the call to Roy. I don't recall discussing it with others on the Court, though I probably talked to one or two.

In time, I came to sense that the other seven Justices had also kept their mouths shut [we didn't have to ask who it was who had leaked the vote], and that the reporter had enough integrity that he would not publish the story unless he had it confirmed.

I and others knew we should not talk out of school. Somehow this time it was personal.

It was not so much that we knew Roy would have been sad to hear that one of us had let him down. A published report of what that reporter told me that Thursday night would have demeaned the Court as an institution in the public eye. We would have been seen as no more than politicians.

We knew Chief Justice Lee would have kept a stiff upper lip, but that deep down it would have broken his heart.

One of my favorite RNL cases was the saga of Mose Dantzler and his efforts to buy beer in Hattiesburg where it was legal to do so and transport it to his rural home in the privacy of which he could lawfully enjoy it.15

Previously known to law enforcement, mighty Mose was arrested, charged and convicted of illegal possession in a "dry" part of Lamar County. By then Chief Justice, Roy wrote and circulated a majority opinion, affirming.

Seeing the draft, I wanted so badly to walk into his office and ask only the one word question, "Roy?!?!?" I know at least two other members of the Court had the same unacted upon urge.

We all knew that RNL slipped in and out of a particular Jackson area liquor store with some frequency, to assure that his home in Scott County was always well stocked, a place where he could appropriately share camaraderie with family, friends and guests.

We were pretty sure that just about everyone Roy knew of his familiar practice.

We knew no law enforcement officer dared stop the liquor laden big boat of a Lincoln Continental of Chief Justice Lee while it was motoring through "dry" Rankin and "dry" Scott County en route home.

We also knew, if we made the visit to his office, we'd be met with the inimitable Roy Noble Lee grin.

I never knew a man who could say so much with a silent grin.

He well knew he had the ultimate and all sufficient defense, that he knew human nature and each of us well enough to know the foibles of the rest of us were equal to if not in excess of his own.

And he knew we knew he knew.

He wasn't a scholar of the law. He wasn't a great writer. I used to cringe at his familiar recitation of a procedural circumstance followed by "but the trial judge will not be put in error for …"

It was about the courthouse to Roy Noble Lee. He used to tell of going to school across the street from the courthouse, how when school was out he would go to the courthouse to see what was happening. Like the moth to flame, Roy felt the pull of the courthouse.

Of course, his father was a lawyer. But you sensed Roy had grown past his father in seeing farther that something special about the courthouse, any courthouse.

I doubt Roy Noble Lee read a lot of William Faulkner, though I don't know that. I've an idea Faulkner summed up what the courthouse meant to Roy and his view of a community

"because it was theirs, bigger than any because it was the sum of all, and being the sum of all, it must raise all of their hopes and aspirations level with its own aspirant and soaring cupola, so that, sweating and tireless and unflagging, they would look about at one another a little shyly, a little amazed, with something like humility too, as if they were realizing, or were for a moment at least capable of believing, that men, all men, including themselves, were a little better, purer maybe even, than they had thought, expected, or even needed to be." 16