Chief Justice Waller's commemorative Bicentennial address 1

Posted December 2017In considering the Bicentennial of Mississippi's judiciary and legal profession, the courthouse must be the starting point. In nearly every Mississippi county, the first major public structure constructed in the county was the courthouse. Not only is the structure significant architecturally, but it is usually located in a very prominent location in the center of the county seat with abundant green space, all of which signifies the importance of the courthouse. In Requiem for a Nun, William Faulkner would speak of the courthouse:

But above all, the courthouse: the center, the focus, the hub; sitting looming in the center of the county's circumference like a single cloud in its ring of horizon, laying its vast shadow to the uttermost rim of horizon; musing, brooding, symbolic and ponderable, tall as cloud, solid as rock, dominating all; protector of the weak, judicata and curb of the passions and lusts, repository and guardian of the aspirations and hopes …

The courthouse is where life, liberty and pursuit of happiness, as framed by the original writers of the Constitution and Bill of Rights of the United States, are protected and enforced. While it is up to the judge, and the jury, to make the decisions, it is the lawyer, the advocate, who, through investigation, research, and preparation, makes sure that the client has his or her day in court, who stands and speaks for the client, who argues for the fair, efficient and independent administration of justice. And the courthouse is the place where the pursuit of justice is carried on in public view and the results are recorded for posterity. This speech will highlight examples of justice in the courthouse.

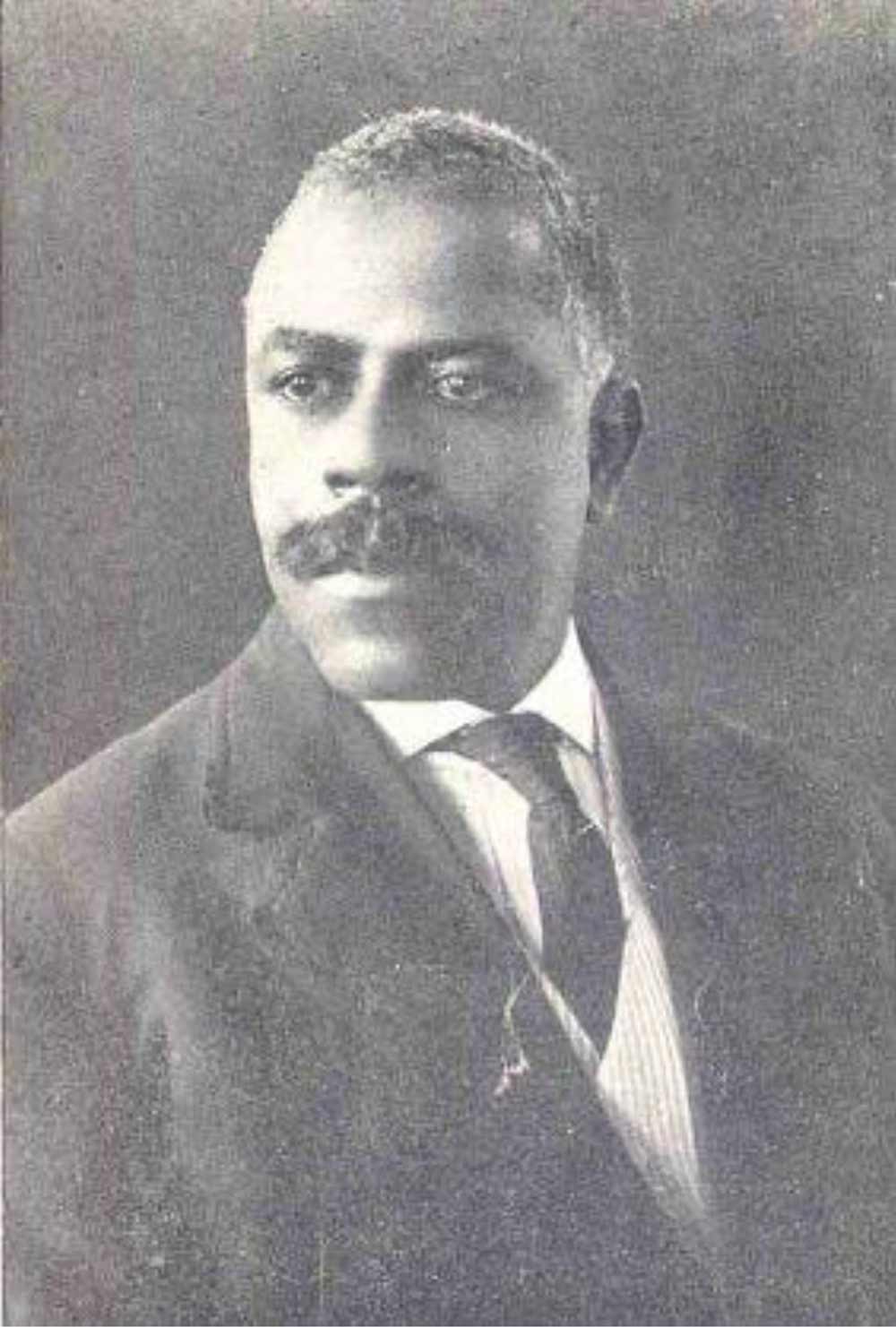

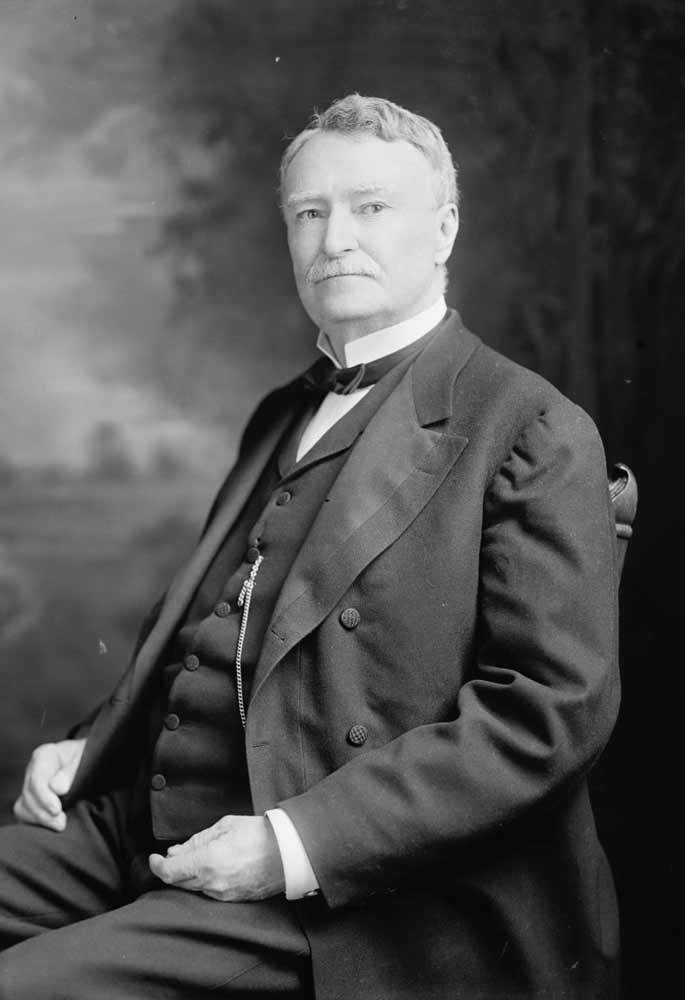

The Reconstruction period witnessed the first public participation of African Americans in the governmental process, including the practice of law. The Constitution of 1868 was the first and only constitution in the history of the State ratified by a popular vote. And it largely reflected a super-majority of Republicans. The new constitution did not necessarily reflect a change of attitude of many white citizens to these newfound freedoms. Nonetheless, African Americans persevered in public life, including the practice of law. One example of courageous action bears publication. Anselm McLaurin, a white Brandon attorney, sponsored Samuel A. Beadle, an African American, for his examination to become a member of the Bar. Back then, the examination took place in open court before the chancellor. The local Bar was invited to attend and participate. McLaurin's first attempt to sponsor Beadle was rebuffed by the chancellor because of Beadle's race. Not to be deterred, McLaurin returned, this time bringing with him Patrick Henry, under whom Beadle had studied the law. This time the examination was permitted to proceed. Beadle was given a rigorous examination by the chancellor, followed by questioning from members of the Bar, which included twenty-six attorneys from Jackson.

At the conclusion of the interview, Beadle was admitted to practice. His friends and supporters lifted him to their shoulders and carried him around the courthouse to celebrate the occasion. McLaurin would later be elected Governor and U.S. Senator. Henry would be elected to Congress. Beadle enjoyed a successful law practice in Jackson, Vicksburg, Natchez, and Canton, though racism prohibited his work in other counties.

McLaurin used the public forum of the Courthouse persevering against prejudice to argue that law and justice required that his friend Samuel Beadle be able to sit for an examination.

James Z. George was the architect of the Constitution of 1890, which was primarily designed for control of the government by Democratic elites to the exclusion of not only African Americans but also poor whites. Though many would call the provisions for the appointment of all judges enlightened, modifying the selection of judges to elections was one of many provision shaping the constitution into what we have today. The constitutional amendments of 1916, requiring elections and increasing the number of Supreme Court Justices to six, define the fundamental architectural changes to mark this period.

While the Mississippi Constitution did not limit or restrict black lawyers, the changing political environment did. Racial hostility saw an upturn under the ugly, race-baiting rhetoric of Governor James K. Vardaman, who served as Governor from 1904–1908, and the number of black attorneys would steadily diminish.

While the black members of the Bar struggled, this era did witness the emergence of female attorneys. Leading the way was Susie Blue Buchanan, who became the first female lawyer admitted to practice before the Mississippi Supreme Court in 1916 and who was an active member of the Rankin County Bar until her death. Lucy Somerville Howorth became the first female to be called "judge" when she was appointed United States Commissioner for the Southern District of Mississippi in 1927. The position of United States Commissioner was the forerunner of today's federal magistrate judge. And Zelma Wells Price became the first woman to serve as a Mississippi trial judge in 1955. Notably, Wells also led efforts to include women in jury venires. In the ensuing years, countless women have left their mark on the Mississippi judiciary, including Lenore L. Prather, our state's first female Supreme Court Justice and Chief Justice, who gave leadership to the design and funding of the Mississippi Supreme Court Courthouse. A second, Mary Libby Payne, holds the distinction of having served in all three branches of the Mississippi government and was the founding Dean of Mississippi College School of Law, as well as the first female judge on the Mississippi Court of Appeals.

One example of justice in the courthouse during this transitional period was provided by Justice Virgil Griffith. His vigorous dissent in Brown v. State2 in 1935 ultimately resulted in a unanimous reversal of three convictions by the United States Supreme Court. That the defendants' confessions were brutally extracted without any other inculpatory evidence was not disputed. The heinous conduct committed to coerce the confession of Brown and his co-defendants included a near-fatal hanging, with the rope burns on the defendant's neck visible to the court. Though the admission of the confession was objected to and evidence of duress was presented in the defendant's case-in-chief, the Mississippi Supreme Court held the failure to move to exclude the confession was fatal, and the issue was procedurally barred on appeal. To this, Justice Griffith responded:

If this judgment be affirmed by the federal Supreme Court, it will be the first in the history of that court wherein there was allowed to stand a conviction based solely upon testimony coerced by the barbarities of the executive officers of the state, known to the prosecuting officers of the state as having been so coerced, when the testimony was introduced, and fully shown in all its nakedness to the trial judge before he closed the case and submitted it to the jury, and when all this is not only undisputed, but is expressly and openly admitted.

The United States Supreme Court unanimously reversed the judgment of the Mississippi Supreme Court in an opinion by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes.3 Justice Griffith was mentioned by name in the opinion, and much of his dissent was quoted in full as the opinion of the Court. Justice prevailed because of Justice Griffith's courage to follow the law.

By constitutional amendment in 1952, the membership of the Supreme Court was increased from six to nine. This period is highlighted by the advancement of civil rights through the legal system, which is best illustrated by four events.

The first was the re-emergence of black lawyers in Mississippi in the 1960s from Depression-era lows. R. Jess Brown is credited with filing the first modern civil rights lawsuit attacking literacy tests for voter registration in Mississippi. Brown, along with Jack Young and Carsie Hall, led the way for the re-establishment of African Americans into the mainstream of the Bar. The courageous pursuit of justice by these attorneys inspired future generations, such as Reuben V. Anderson, Mississippi's first black Supreme Court Justice, Henry T. Wingate, the state's first black federal judge, and Leslie D. King, one of the original members and Chief Judge of the Mississippi Court of Appeals. Justice King currently serves as a member of the Supreme Court.

Second was the first serious and ultimately successful prosecution of Byron De La Beckwith by District Attorney William L. Waller, Sr., for the murder of Medgar Evers. The first trial and subsequent retrial both resulted in mistrials, leaving open the possibility of justice for another day. And the record from the first trial would provide the core evidence needed for a conviction years later.4 But the precedent was set, hate crimes would no longer be tolerated in Mississippi.

Third, the admission of James H. Meredith into the University of Mississippi would mark the end of state-sponsored segregation and the opening of public institutions, including courthouses, to all citizens. Fittingly, it was R. Jess Brown who represented Meredith in his battle to break the race barrier in Mississippi schools.

Finally, Mississippi was "readmitted to the Union," so to speak, when the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit began holding court in Jackson in 1967. Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit and former Mississippi Governor James P. Coleman was instrumental in this event, because he believed that it was important for residents in every state in the circuit to have access to a courthouse. As noted in his oral history, Coleman explained to his colleagues, "You [the Fifth Circuit] are sitting in every state in the circuit but Mississippi. I think the people of Mississippi would be improved by being given the opportunity to see that y'all don't have horns and I think it would be good for y'all to see the people of Mississippi and see that they are no different that these other states you are sitting in." This important accomplishment is yet another example of the importance of an open and accessible judicial system.

The Supreme Court began to lay the foundation for modern judicial procedure in the 1970s, and the cornerstone of this foundation was the Court's decision in Newell v. State in 1975.5 Prior to Newell, it was generally accepted that the Legislature had exclusive control over rules of judicial procedure. But in one of the boldest assertions of authority ever adopted by an American court of last resort, the Court in Newell struck down a procedural statute governing jury instructions, finding that it interfered with the judicial branch's constitutional mandate for the fair administration of justice. The statute at issue prohibited the trial court from adding any jury instructions that were not offered by the parties. In Newell, this resulted in the jury not being instructed on the burden of proof in a criminal trial. In striking down this statute, it was established for the first time in Mississippi that the inherent authority to prescribe rules of judicial procedure rested with the Supreme Court, not the Legislature.

Bicentennial banquet speaker Chief Justice William L. Waller, Jr.

The assertive stance taken by the Court in Newell may have faltered under the scrutiny and opposition it ultimately faced if not for the efforts of Chief Justice Robert G. Gillespie and Associate Justice Neville H. Patterson, the author of Newell. Chief Justice Gillespie was a model of perseverance in his own right, having been forced out of law school by poverty and a career in law enforcement by tuberculosis, but not before participating in the gunfight that ended the life of the notorious gangster John Dillenger. He and Justice Patterson understood the importance of the Court's undertaking in Newell, so they worked tirelessly to ensure that the opinion of the Court was unanimous.

In 1981, the Supreme Court, now led by Chief Justice Patterson, formally acted on the authority it had announced in Newell by adopting the Mississippi Rules of Civil Procedure. This action was met with immediate confrontation, with the Legislature considering constitutional amendments to limit the Court's rulemaking power, threatening the Court with budget cuts, and even pursuing the removal of pro-Rules justices from the bench. But the Legislature ultimately relented, and the Supreme Court has since asserted its inherent rulemaking power to adopt rules of evidence, rules of appellate procedure, rules of circuit and chancery court practice, and a variety of other procedural guidelines. And under the leadership of Justice Ann H. Lamar, the Court adopted its first comprehensive set of Rules of Criminal Procedure in July of 2017. These rules exist only because the Supreme Court was willing to take a stand for the fair, efficient, and independent administration of justice in Newell, in the face of stiff political pressure.

The "modern" period of the Mississippi judiciary is highlighted by bold innovations to increase access to justice, none of which was more critical than the creation of the Mississippi Court of Appeals in 1994, in the face of a choking backlog of cases in the Supreme Court. The heroic message of Chief Justice Roy Noble Lee before the Legislature and his dogmatic insistence on reform prevailed, and the Court of Appeals ultimately has provided the citizens of this state with a more timely and responsive court system.

The advent of "problem-solving" courts, such as drug courts, has changed the lives of many Mississippi citizens for the better and serves as another reminder of how justice is carried out in the courthouse. The first drug court pilot program was led by then state Circuit Court Judge Keith Starrett in 1999. Drug courts provide a unique opportunity to address the very real problem of drug addiction, steering individuals into treatment and self-improvement rather than incarceration. This program has been one of the most successful innovations to our judicial system, as it has lowered recidivism rates while paying back money to the counties and reducing the amount that would be spent on incarceration.

The implementation of technology in our court system has brought the judiciary into the digital age and made it more accessible to Mississippians. Chief Justice Edwin Lloyd Pittman spearheaded the adoption of rules to allow cameras in the courtroom, a change that opened our courthouses to the public. And Chief Justice James W. Smith, Jr., began the groundwork that led to the creation of the Mississippi Electronic Courts system, a comprehensive electronic filing system that is used by our appellate courts and is being implemented throughout our trial courts as quickly as possible. Electronic filing is critical because it gives practitioners and the public around-the-clock access to court documents. These innovations have earned Mississippi recognition for having one of the most transparent judicial systems in the country.6

The judicial system can be truly fair only if it is equally accessible to the rich and the poor. Realizing the need for greater access to courts in civil cases, several organizations have established programs to provide legal services and funding for low-income clients. In 2006, the Mississippi Supreme Court worked with the Mississippi Bar and the Bar Foundation to create the Mississippi Access to Justice Commission, which serves as a unifying entity to bring together providers of legal services and improve access to civil courts for the poor. The early leadership of the Commission included former Justice Jess H. Dickinson, as well as Chancellor Denise S. Owens, one of the state's first African American female chancellors, and Joy Phillips, the first female President of the Mississippi Bar. The Commission has helped to implement new procedures to provide funding for and legal services to the poor. These innovations include requiring attorneys to report pro bono hours and mandatory IOLTA 7 accounts for escrow funds, requiring all interest to be used to support access to the courts. And in conjunction with the Commission and other legal-services groups, the Mississippi Volunteer Lawyers Project has begun to promote Pro Se Days throughout the state to generate public awareness and provide legal services to hundreds of low-income citizens.

Maintaining the integrity of the courthouse during this modern period of the judiciary is perhaps best symbolized by the heroic actions of Judge Henry Lackey, who agreed to be the point man in a sting operation memorialized in Curtis Wilkie's book The Fall of the House of Zeus.8 In 2007, a colleague of famed tort lawyer Richard "Dickie" Scruggs approached Judge Lackey and offered a bribe in exchange for a favorable ruling in one of Scruggs's cases. Judge Lackey relayed this information to federal prosecutors and then participated in an undercover operation that resulted in Scruggs's arrest and conviction for conspiring to bribe a judge. In what was otherwise a dark moment for the legal community, Judge Lackey's courage under pressure helped restore public confidence in the justice system.

It is the Courthouse that has and will always be the forum for the fair, efficient, and independent administration of justice in public view, recorded for posterity, and subject to the right of appeal.