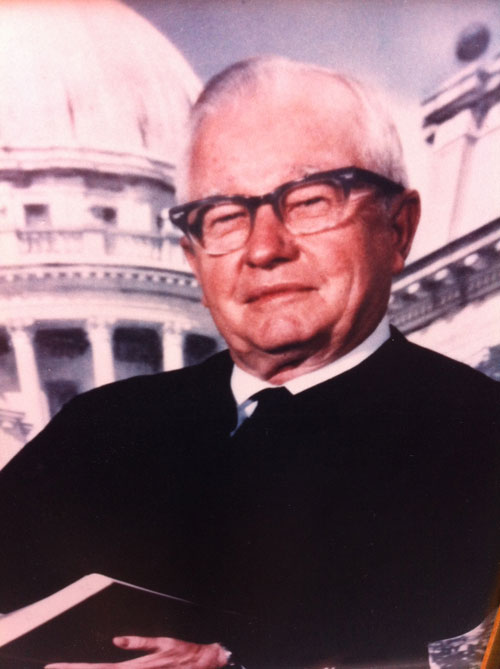

The Storied Career of Former Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Noble Lee

Article by Chris Shaw Featured Author

Posted February 19, 2013“Many men, including this writer, feel that a person who has never seen squirrels jump from limb to limb in the deep swamp on a frosty Fall morning; or has never heard a wild turkey gobble in April or seen him strut during mating season; or has never watched a deer bound through the woods and fields, or heard a pack of hounds run a fox, or tree a coon (raccoon); or has never hunted the rabbit, or flushed a covey of quail ahead of a pointed bird dog; or has never angled for bass or caught bream on a light line and rod, or taken catfish from a trotline and limb hook; has never lived.”

Justice Roy Noble Lee — Strong v. Bostick, 420 So. 2d 1356, 1364 (Miss. 1982)

The stories of former Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Roy Noble Lee’s are the stuff of legend.

There is, of course, the time when he tried his first criminal trial in the 1920s. He was 19. He had no law degree, no training, and no license.

“I was sitting in the courtroom in Brandon and a case was called where a man was charged with assault and battery,” Lee said in an interview on Mississippi Moments for the Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage (“the Center”) and the University of Southern Mississippi. “I jumped up and said, ‘judge, I’m not a lawyer, but I’d like to defend him.’ The judge said ‘ok, son. I’ll give you 15 minutes to coach up your witnesses, if you’ve got any.’ I didn’t have any witnesses.”

When Lee returned, the courtroom was packed. After closing arguments, the jury returned with a verdict of not guilty.

“I had ridden over from Forest with my father, and when we got into the car he hadn’t said a word and I hadn’t said a word,” Lee told the Center. “He finally looked at me and said ‘son, you’re going to make a lawyer one day.’”

And so he did. Of course, it was all he had ever wanted to do. He grew up around it. It also didn’t hurt that his father, Percy Mercer Lee, was a lawyer, District Attorney, Circuit Court Judge and later served on the Mississippi Supreme Court from 1950-1965 and as Chief Justice from 1964-65.

“From the time I was 9 years old I wanted to be a lawyer,” Lee told the Center. “I never thought of doing anything else. The school was adjacent to the courthouse, so each day when I got out of school I would go over to the courthouse. I wanted to hear everything that was going on. Those were the days when courtrooms were full of people. I loved it. My daddy never pressured me to be a lawyer, but he made me available to the law.”

Lee joined the Mississippi Supreme Court in 1976. He served as chief justice of the Court from 1987 to 1992 when he retired from the bench. In his term on the Court, Lee is credited with creating the Mississippi Court of Appeals, the administrative office of the courts, and being a quiet, but powerful force for the judiciary in Mississippi. The important decisions he participated in as a supreme court justice are too numerous to mention.

“He was just visionary,” said former law clerk Amy Whitten, who also served as Lee’s courtroom administrator. “He helped create the architecture for the 21st century court system. He also worked on improving the pay scale for judges and district attorneys. As chief justice, he felt like he was the advocate for everyone that worked in the third branch, rather than having them have to advocate for themselves.”

But perhaps Lee’s greatest legacy is his legendary quiet, steely demeanor and the influence it gave him throughout the State of Mississippi. He could twist arms with his eyes. He used that influence to get things done, including the Court of Appeals “which would have taken 50 years to get done nowadays,” said Whitten.

“He was so quietly strong that he just never garnered a lot of opposition,” said Whitten. “He would plant and stand and other things would back up, but he was always such a gentleman.”

Lee succeeded Justice Neville Patterson as the chief justice. Patterson is described as the quintessential inside-the-court politician, friendly to everyone with the skills to work the crowd.

“Roy was the opposite,” said former Supreme Court Justice Jimmy Robertson. “He had a way of earning your respect. You respected Roy and you liked Neville. He would always do his best to keep a poker face and not let anyone know what he was thinking. When we would have an en banc conference and go around the court, he would listen and loved knowing what everyone else thought about the case before he would say a word.”

Lee loved hunting and the outdoors almost as much as he loved the law. Robertson recalls that the Court schedule revolved around the various hunting seasons. He would be seen sometimes in the parking lot “pulling out dead turkeys out of his trunk” to show others, said Whitten.

He would even hunt some mornings at daybreak — in his tie — before making the 45-mile trip west along Interstate 20 from Forest to Jackson.

“We called that the 90-mile rule,” said Whitten. “Whatever decisions we were trying to get him to make, he would drive 45 miles to Jackson and back before making a decision. I don’t know if he ever knew that.”

Robertson learned first-hand about the quiet, but effective influence Lee could wield over those around him, especially when it came to his passion for hunting. In 1984, a criminal case involving headlighting deer was appealed to the Supreme Court from Leflore County. But Justice Lee was not assigned the case. Instead, it was assigned to one of the newest members of the Court at the time, Robertson, who had never been hunting in his life.

“Roy being the hunter learned about the case and was very interested,” said Robertson. “I’d been at the Court long enough to know he was not a guy that would normally come visit with you in your office, but he came to my office and said ‘Jimmy, I understand you’ve drawn the deer headlighting case. Now, you know this is a really important case and I know you’ll give it the attention it deserves. It needs to get some publicity.’”

For the next few months, Justice Lee appeared in Justice Robertson’s chambers on five separate occasions to remind him this was a case where a message needed to be sent.

“Many of the other justices were politicians, and they would come by the office and sit and talk and tell jokes,” said Robertson. Justice Lee was not one of those justices. Rather, “he was very close to the vest, but each time he visited he would mention the case,” said Robertson. “He was a true hunter and he thought deer poachers and those who headlighted deer should be put under the jail.”

Justice Lee’s silent, but effective authority won over the newly-minted Supreme Court Justice. The opening paragraph of the deer headlighting case of Pharr v. State reads as follows:

Headlighting deer is a sorry form of human behavior made unlawful by the wildlife conservation laws of this state. The deer, usually a doe, hit with the blinding light stands stupified and is slaughtered. In addition to his unsportsmanlike conduct, the poacher operates at night and endangers other each time he fires. He is of Snopesean genre.

Justice Lee’s point was made, and “Roy never mentioned the story again,” said Robertson.

But as strong as his personality was, Lee never allowed himself to be forever wedded to all of his original notions. Whitten was his first female law clerk, and “someone really had to talk him into me,” said Whitten. “He was so traditional, and had not been around a woman who was not a wife, mother, or secretary. When I would tell him what the law was, you could tell he was having to wrap his mind around that.”

Yet he hired Whitten when the job of court administrator later became available, and she stayed with Lee until he retired in 1992.

“That’s another feature a lot of people never saw or understood,” said Robertson. “Just because he came in with one view didn’t mean he wouldn’t change his mind,” said Robertson, recalling Lee’s initial opposition to the adoption of the Mississippi Rules of Civil Procedure. “But that view better carry the burden of proof to change his mind.”

Lee’s legacy and legend was made off the bench as well. He practiced law in Forest before joining the Mississippi Supreme Court, in private law practice and as a district attorney in Scott County. He made his mark as one of the most prolific courtroom lawyers in the state and served as the first president of the Mississippi Trial Lawyers Association.

“In my 28 years as a federal judge, I have not seen a better trial lawyer,” said federal District Judge Tom Lee of his older brother by 25 years, who swore the younger Lee in and spoke at his investiture. “He had a state-wide reputation as a superior trial lawyer before he went to the bench. He was called upon to defend capital cases from around the state. He was not a good, but a great trial lawyer. There was no better lawyer in Mississippi.”

“Intellectually, he just blew me away,” said Sid Salter, former publisher of the Scott County Times in Forest. “He was scary smart, but not pretentious. He could make the most ignorant, uneducated person in the county feel important. He just had the knack about him.”

During his tenure on the Court, Lee never once moved to Jackson and probably never even thought about it. He was a champion for his hometown of Forest, where he still lives today at 97. He was a confidante of a number of mayors in Forest for years and helped use his influence to get things done in Forest. He was “the kind of person small towns cannot do without,” Salter said.

But no matter the acclaim he garnered at the top of the Mississippi judicial heap, he was never too far away from his Forest roots.

“He was really kind of a quiet guy,” said Salter. He was not a guy to do a lot of high society stuff; he did what he had to do and what his wife made him do. If I ran into him at the post office on Saturdays, I never felt like I was talking to Judge Lee. He was just Roy Noble.”